Note: My post can also be found on the FireEye Threat Research Blog

On red team engagements, Mandiant consultants are often tasked with identifying and obtaining access to critical Unix systems within our client’s environments. The objectives may include obtaining payment card data on point of sale terminals or accessing intellectual property residing on Apple MacBooks.

Since Unix systems are typically not domain-joined, locating and authenticating to them can be a challenge. In fact, current methodologies often rely on luck. Typically, this can include:

- Examining live hosts not enumerable through Active Directory.

- Running netstat across all domain-joined computers and looking for active connections over common Unix-communicating ports.

- Performing port scans for services indicative of a Unix host.

- Searching Active Directory for groups such as “Linux Admins” or “Mac Admins” and identifying their members’ workstations and active sessions.

- Identifying non-AD LDAP instances and hosts associated with them.

In this blog, I address a new approach to finding Unix systems using a small, purely PowerShell tool we created called SessionGopher.

Our thought process was simple: while most Unix systems are off-domain, they are often accessed and managed by domain-joined Windows systems. These Windows systems typically have remote access tools installed on them that would suggest they communicate with Unix systems, and these tools leave behind valuable artifacts that can help consultants both discover and exploit the Unix systems. SessionGopher is designed to identify these remote access tools and extract any auxiliary information about the hosts to which they connect.

Where It Happens: The HKEY_USERS Hive

The HKEY_USERS hive is a Windows hive that contains persistent information about users who have interactively logged on to the system. For each user that authenticates to the system, Windows creates a user subkey at location HKEY_USERS<SID>, where

Amazingly, within these user subkeys reside saved session information for some of the remote access tools discussed earlier. If a user creates a session in WinSCP, a file transfer client often used to communicate with Unix systems, and then saves that session, the entire saved session gets stored in the Registry under that user’s

HKEY_USERS\<User’s SID>\Software\Martin Prikryl\WinSCP 2\Sessions\<Session Name>

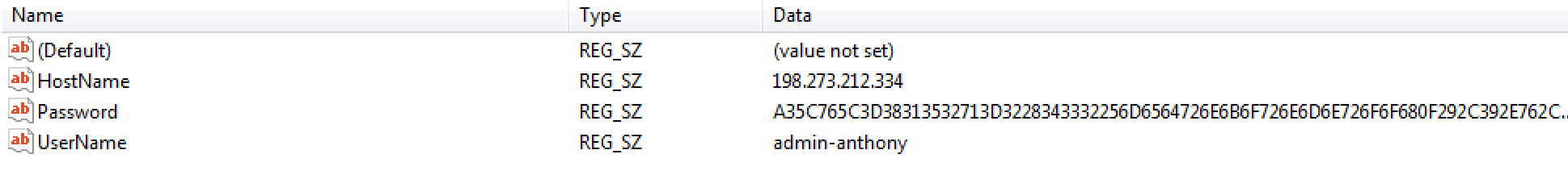

Using regedit, a graphical interface for the Windows Registry, we can examine the contents of one of these sessions.

Figure 1: A WinSCP saved session in the HKEY_USERS hive

By default, the WinSCP password from Figure 1 is obfuscated by several bitwise operations, not encrypted, unless the user explicitly creates a master password to protect these registry values.

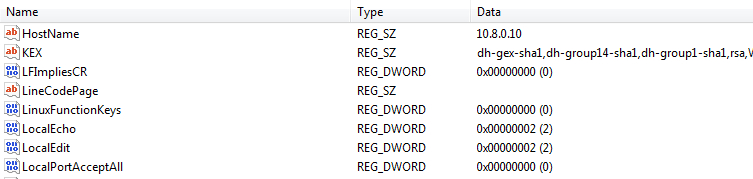

Similarly, PuTTY, an SSH client for Windows, stores its session information as a separate subkey:

HKEY_USERS\<User’s SID>\Software\SimonTatham\PuTTY\Sessions\<Session Name>

While PuTTY does not store passwords, it can store the hostnames to which the client connects, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: A PuTTY saved session in the HKEY_USERS hive

A plethora of remote access tools like these exist which store their saved session information in the user’s HKEY_USERS subkey. Enumerating the domain for systems with these artifacts provides an educated guess as to where Unix systems may be hiding, potentially some credentials, and the hosts that serve as jump boxes to those Unix systems.

Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI)

In developing a post-exploitation tool, using WMI’s remote registry querying functionality to extract these Registry-based saved session artifacts made sense. Our tool SessionGopher leverages WMI to query each SID found in the system’s HKEY_USERS hive for the artifacts discussed earlier.

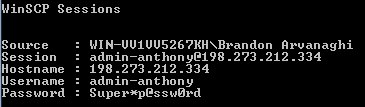

When a master password is not used, SessionGopher automatically deobfuscates WinSCP saved session passwords, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: SessionGopher’s built-in WinSCP password deobfuscator

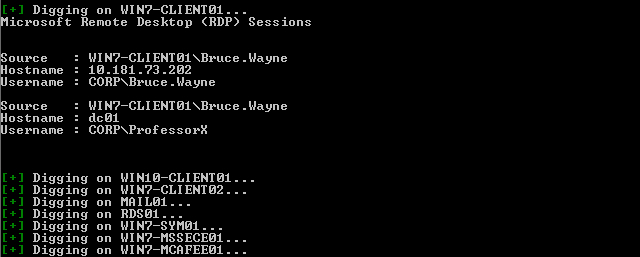

On top of WinSCP and PuTTY, SessionGopher extracts saved RDP session data from each user’s HKEY_USERS subkey. This expands SessionGopher’s functionality from strictly finding Unix systems to also identifying systems that may serve as jump boxes to different subnets. Figure 4 demonstrates SessionGopher returning saved RDP sessions on remote host “WIN7-CLIENT01” when run against a set of domain computers.

Figure 4: SessionGopher discovering saved RDP sessions when run across a domain

Expanding Analysis Methodology

Certain remote access tools such as SuperPuTTY and FileZilla store saved sessions as files rather than in the Registry, so SessionGopher also searches remote filesystems for those default file locations and extracts saved passwords when stored. In -Thorough mode, SessionGopher searches the entire remote filesystem for PuTTY private key (.ppk), Remote Desktop Connection (.rdp), and RSA Soft Token (.sdtid) files.

Currently, SessionGopher looks for artifacts from the following sources:

- WinSCP saved sessions

- PuTTY saved sessions

- RDP saved sessions

- FileZilla saved sessions

- SuperPuTTY saved sessions

- PuTTY .ppk Files

- Microsoft .rdp Files

- RSA .sdtid Files

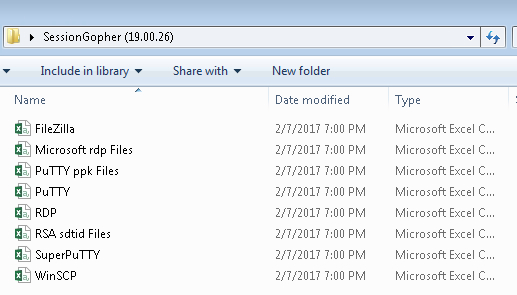

Running SessionGopher across targeted systems on a domain with the –o flag can nicely synthesize all session data into .csv files, allowing the user to keep track of the source computer and user account that led to the session’s discovery. Figure 5 shows SessionGopher’s output folder when run with –o.

Figure 5: Folder of .csvs created by SessionGopher’s –o flag

The fallacy in searching for Unix systems is that if they are not domain-joined, interrogating domain systems for clues provides little insight. As with any internal resource, Unix systems often require management and communication with the corporate domain. The Registry found on each of these domain-joined systems can serve as a trail of breadcrumbs to the exact location of these Unix systems, and to any segmented host of interest.

The tool was created by me, Brandon Arvanaghi. Any subsequent updates to the version found on FireEye’s GitHub can be found on my personal github.